Code reviews are an essential part of the software development lifecycle. Virtually the majority of tech companies, from giants to startups, advocate for code reviews in the pipeline, and it is generally accepted that they contribute to better code quality and more accountability over what is released to production.

While in most open-source projects (thankfully), code reviews were standard practice long ago, it was GitHub’s Pull Request feature that sparkled mass adoption across the IT industry.

Why is this important ? #

The main idea behind a code review is to ensure that at least two engineers collaborated on any change in the code base, increasing quality and accountability. As a developer you’re probably reviewing your peers’ code as much as writing your own (At least you should 😀), and pull/merge requests are usually the stage where you’ll exchange more feedback and knowledge with your peers about the feature being delivered.

The distributed nature of the pull request process allows code reviews to be written and asynchronous, which is what happens most of the time, so it is important to make them as clear and concise as possible to make sure that your peer understands what’s being done and facilitate the review. Obscure pull requests lead to misunderstandings, lack of context and ultimately bugs. This becomes even more evident on remote teams with weaker communication habits, or low timezone overlap.

Optimizing your PR’s readability #

We all think and communicate differently from each other, even within the same cultural boundaries. Translation and interpretation issues happen all the time, so the best strategy to get a smooth code review, with no surprises, is to start preparing it from the moment you begin writing code.

Tidy up your commit history #

When building software, one thing we usually do is to use a divide and conquer approach and implement the feature step by step. If we’re able to mirror this strategy into the commit history, it will help the reviewer understand the timeline of events, and review the commits individually. Additionally, good commit messages will make the history self-descriptive, and the reviewer will know what to look for.

Let’s suppose we have a user microservice, and our task is to include the user’s last name in the get user details endpoint. Here’s what I think it would be a good commit history:

* 54bfc23ab Add lastName to UserEntity and update UserRepository to fetch from db

* 43ba765a5 Add lastName to UserDTO and update UserController fetch from UserRepository

The idea is to create small commits where a single component is changed, as well as the tests it affects. The commit message itself gives a hint of what files were changed, so that whoever reads it can easily understand what to look for. After clearing that commit, the reviewer can mentally close that context and jump to the next as if she was developing the feature herself.

To make this point clear, here are some patterns that you probably have come across, which I think aren’t review friendly (The names are made up):

Do then test #

* 54bfc23ab Add lastName to user

* 43ba765a5 Fix tests

* 32aa54db7 Fix tests

I’m not advocating for TDD here, that’s a touchy subject 🔥, but I just think that on a step-by-step approach it makes sense to change all the files related to a specific context and the tests are part of it. If the changes made to UserRepository test are in the last commit, it will force the reviewer to context switch back to a step that was already cleared.

Sniper #

* 54bfc23ab Add lastName to user

One shot commit histories are also not spectacular to review because they contain too much information, as opposed to a divide and conquer approach where we would review small changes step by step. It’s also difficult to know where to start, since all the files were changed in the same commit

#YOLO #

* 54bfc23ab First draft

* 43ba765a5 Fix bug

* 32aa54db7 Fix tests

* 24ab567a8 Fix another bug

This is the typical case where someone didn’t test the code locally and only realized they’ve made a mistake when the pipeline failed or there is a bug in the sandbox environment. While this obviously can happen even if you took all precautions, you should avoid polluting the commit history while trying to fix mistakes. If there is no other way, maybe it can be a good idea to use rebase and squash commits before creating the PR.

If you’re able to guide the reviewer with your commit history, half of the work is done because she will be able to keep up with your line of thought. Descriptive messages are key to this, but organizing commits into logical steps can also be very helpful.

Fix conflicts ahead of submitting the PR #

Merge conflicts are a frequent issue, especially in projects with lots of developers and small code bases. While it might not impact the review itself, it is a good practice to keep your code up to date with the main branch, so that the merge runs smoothly. Depending on your team’s process, you might find yourself in a situation where you need to fix the merge conflicts and ask the reviewer to go back and approve the PR again because you couldn’t merge it in the first place.

Use Rebase instead of merge #

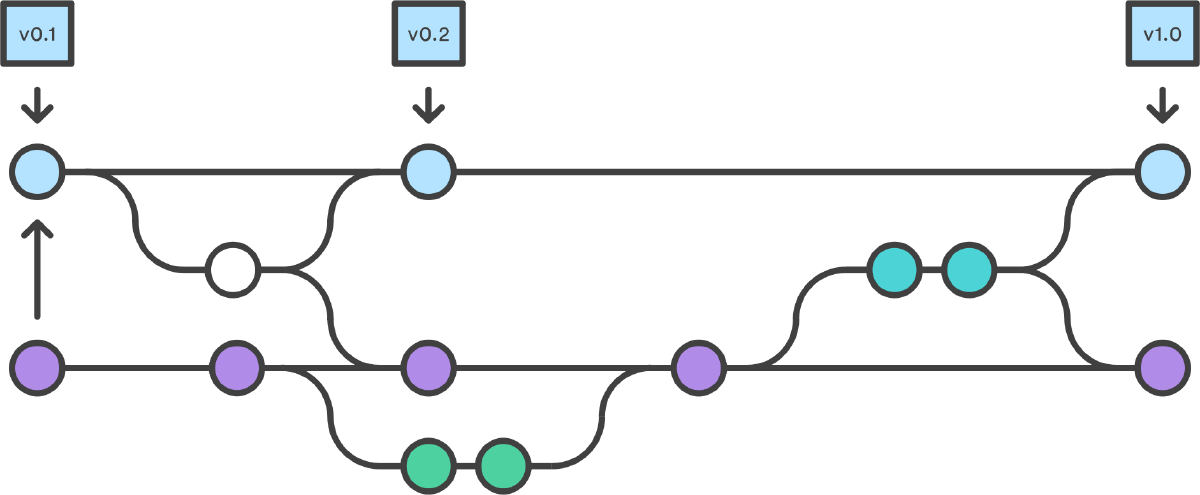

A very common way of keeping a branch updated is to merge the main branch into the feature branch ahead of the review or at some point in time. While this standard practice for many, there is a downside which is the commits it adds to the history after the merge.

* 54bfc23ab Add lastName to UserEntity and update UserRepository to fetch from db

* 43ba765a5 Add lastName to UserDTO and update UserController fetch from UserRepository

* e672eab17 Merge branch 'master' into 'feature/add-last-name-to-user'

Rebase on the other side does a slightly different thing which is to apply all the commits from the main branch into the feature branch, without polluting the history with merge commits (one less thing for the reviewer to care).

* 54bfc23ab Add lastName to UserEntity and update UserRepository to fetch from db

* 43ba765a5 Add lastName to UserDTO and update UserController fetch from UserRepository

The downside to this approach is that it will force you to use push --force-with-lease if your feature branch is already published on the origin.

Don’t commit code formatting changes #

Including code formatting changes in a PR will cost the reviewer a significant amount of time figuring out what parts of the code have actually changed. If you find yourself doing this it’s a sign that either there is a misalignment between you and your team, or the project doesn’t have an automated code formatter yet. There are a bunch of tools that you can plug in to your IDE or commit hooks like Prettier and EditorConfig and avoid committing formatting changes. The only important requirement for this to work is that everyone in the team uses an equivalent formatting setup so that all code is in the same format when committed.

Side note: Don’t fall into the trap of actually discussing those standards as you and your team will most certainly burn precious amounts of time not reaching an agreement. I find it more practical to use community accepted ones like Google, Facebook or Airbnb code formatting standards.

Comment and document your code #

Use comments wherever the code itself doesn’t make it obvious why you made such a decision. This might even help other developers that come across your code in the future and need some context of why something is happening .

+ for(User u : users) {

+ if(user.isActive()) {

+ // Interrupt the entire process because no user should be active at this point

+ throw new IllegalUserStateException(u);

+ }

+ deleteUser(u);

+ }

Just keep in mind that a comment is another line to review, and too many comments makes the code less readable, so try to avoid redundant comments.

+ // If the user is active, throw an exception

+ if(user.isActive()) {

+ throw new IllegalUserStateException(u)

+ }

+ // Delete the user

+ deleteUser(u)

Documentation on the other side is a bit different, typically public classes and methods should be properly documented so that you can generate decent API docs, however it is also very easy to exaggerate and add documentation to stuff that’s self-explanatory like getters and setters:

+ /**

+ * Gets the user

+ */

+ public User getUser();

My opinion for cases like this is that you’re better off with a simple description in the class header, or no description at all, as the comment doesn’t add any value to whoever is reading it.

+ /**

+ * Provides CRUD functionality over Users on the data store

+ */

+ interface UserRepository {

+ public User getUser();

+ public User createUser();

+ public void deleteUser(User u);

+ }

Include every relevant detail in the PR’s description #

I found several guides for creating pull request descriptions, all of them slightly different from each other but with the same base idea: Try to provide as much context as possible so that the reviewer looks in the right places. I also believe that descriptions with too many sections and details are at the risk of being ignored, so I try to keep them short and objective.

Context #

Explain why this PR exists, what is the current problem and what needs to be fixed. Most teams already have this information on their issue tracker, so it’s obviously a good practice to include a link to it, but it’s an even better one to write a small paragraph so that the reviewer doesn’t need to click it.

This PR closes issue CONN-1023, which is a feature request to add the user's

last name to the get users endpoint in the users microservice

What was done #

The smaller this section is, the better. Usually, I use a list of items to guide the reviewer. These might be similar to the commit list but with complementary information on the design patterns or algorithms used, for example. If these are UI changes, you can record a video or include screenshots, for example, which will be very helpful for whoever is trying to reproduce the fix.

- Changed `UserRepository` to include last name in the db query

- Changed `UserController` to include the new parameter in the endpoint signature

- Updated the documentation

- Created a new integration test

Communicate in a positive way #

I had to put this here, but the idea was actually taken from Anton Chuchkalov’s article. As I mentioned in previous articles, creating a positive culture and having a good relationship with your peers is key to engagement and collaboration. Pull requests or code reviews are just another instance where you and your team need to work together in order to get somewhere. This remarkable quote from Anton’s article sums it all up:

Remember: Code changes are ephemeral - relationships with teammates are what matters

Recap #

Code reviews are standard practice in the tech industry and pull/merge requests on version control platforms are the most common tools for conducting them. The process itself is written and asynchronous, and with the tendency to build geographically distributed teams we are more vulnerable to lack of context and communication issues, which is why it’s so important to write good pull requests.

What do these look like is a widely discussed subject on the internet, and while the above strategies have worked for me, there are certainly different approaches. I believe that every organization and individual is different and therefore my ultimate recommendation is that each should explicitly discuss how to address pull requests and code reviews, in order to develop the framework that best fits their reality.

Other Resources #

- Martin Fowler - Pull Request

- Github - How to write the perfect pull request

- Anton Chuchkalov - How to make a perfect pull request

- Sajal Sharma - How to write a pull request description

- Gonzalo Bañuelos - Writing a great pull request description

- Hugo Dias - Anatomy of a perfect pull request